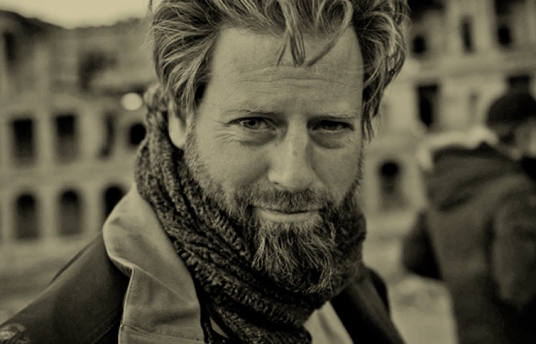

People in Film: Sam French

Jun 05, 2013

Director Sam French has recently returned to the USA after a five-year stint in Afghanistan, where he co-founded the Afghan Film Project, an NGO that transfers professional skills to the Afghan filmmaking community. He made the Academy Award-nominated short film ‘Buzkashi Boys’ while there – you can catch DFI’s presentation of the film at the MIA this weekend. We caught up with him in New York City.

DFI: How did you end up in Afganistan?

Sam French: I went to USC graduate school [in Los Angeles] for film and I met this guy named Martin Roe and we collaborated on a lot of projects. He’s British and he introduced me to a wonderful woman who I fell in love with. She works for the British government and was posted to Afghanistan; I decided to pick up and go to Kabul to follow her. When I got there I fell in love with the country and realised there are a lot of stories to tell there. What you see in the news is bombs and bullets, but [there are] a lot of stories behind the headlines. So I started a documentary film production company called Development Pictures to try to document some of those stories.

DFI: How did the ‘Buzkashi Boys’ project come about?

SF: After a couple of years, my friend Martin came to visit. We had been writing some big-budget science-fiction film script together. We were exploring Kabul, went to Bamiyan where the Buddhas used to be before the Taliban destroyed them. Martin was in awe of the country – and I was seeing the country again through his eyes. We decided to write a script set in Afghanistan. The idea was to tell a universal coming-of-age story, and make it accessible first of all to an Afghan audience, but also an international audience – and to try to show that the people living in that country have hopes and dreams like everyone else.

Then, along with Ariel Nasr and Leslie Nott – who are filmmakers and close friends of mine living in Afghanistan – we decided to [use ‘Buzkashi Boys’] to try to help the Afghan film industry as much as we could. We started the Afghan Film Project, whose mission is to foster the film industry by helping and training Afghan filmmakers. We found 12 Afghan trainees and did intensive training workshops, mentored them with Western professionals on the production, then as the production finished up, we brought our editor over to continue training during post-production. So [the project] was a success even before the film was finished. These trainees have gone on to make their own films and work in the industry – which still needs help.

DFI: So the Afghan Film Project is still up and running?

SF: Yes. We’ve taken a brief hiatus to reorganise the structure, but Leslie and Ariel and I are committed to continuing the programme. We want to transition over the next year to an Afghan-led organisation. It’s tough finding funding for a cultural programme at this time in Afghanistan. These filmmakers we’ve met are passionate about filmmaking. It’s amazing to see, because the film industry was decimated by 30 years of war. When the Taliban came in, they banned filmmaking. A lot of filmmakers fled the country. Now they’re coming back and there’s some amazing talent – I mean, Siddiq Barmak and Atiq Rahimi are making great films over there – but there’s a whole new generation of filmmakers who need training.

DFI: The boys in the film are young, but they interact in an especially adult way – their banter and their way of talking about what’s next for them.

SF: In Kabul, you see street kids everywhere. Something like 75 percent of the Afghan population is under the age of 18. These kids have this 1,000-yard stare – they’ve seen a lot of suffering and poverty around them, so they haven’t really had a childhood. That was front and centre throughout the production. One character is a blacksmith’s son, very poor with not much prospect of a future. He’s best friends with a street urchin who has grand dreams that may or may not be realisable. But even in the face of this poverty, kids can still dream. That was important to us. These are boys on the cusp of being men. We wanted to [look at] the struggle of [deciding] what kind of man you want to be, taking responsibility for figuring out what your future looks like.

DFI: The colour palette uses muted tones. Why that choice?

SF: We shot entirely on location in Afghanistan, which has a stark beauty –there are snow-covered mountains in the background. [So] the colour palette isn’t vibrant; we really wanted to highlight the beauty of the landscape. We had two colours – the green of the scarf and the red of the forge in the blacksmith’s shop.

DFI: It’s stunning. It’s a beautiful thing to be able to take advantage of.

SF: We were fortunate to be able to film in these stunning locations, like Darul Aman Palace. It has been bombed by all sides in the civil war – it’s this tattered remnant of former glory. One of the images I had was a kid walking through the shattered palace with steel girders thrusting into the sky. He’s got a future ahead of him in these remnants of war. Our cinematographer, Duraid Munajim is Canadian – his background is Persian. His eye is amazing and his visual style is great.

DFI: The buzkashi tournament – was it live or did you have to stage it?

SF: Our amazing producer Ariel Nasr really came on board as a true creative collaborator and worked miracles to make the production happen. It’s not easy to film in Afghanistan and Ariel spent a lot of time talking to the right people, getting permission and getting the equipment and the Afghan filmmakers who could make this happen. The idea was to have a two-day shoot of the buzkashi game – the first day would film the action of the game and the kids in the stands; the second day, we were going to shoot with a few riders and create a scene on the field. It was Tuesday and we were supposed to start shooting on Friday, when we were going to shoot the buzkashi match, which they ALWAYS play on a Friday… We got a call on Tuesday night saying they had decided to play on Wednesday. We scrambled and got everybody together and woke up the next morning and it turned out to be the biggest blizzard I’d ever seen in Afghanistan. We went out in this howling snow and shot the match – but we couldn’t do our second day of shooting because [with no snowstorm, the footage] wouldn’t match. But it got some beautiful footage and the buzkashi riders were amazing.

DFI: It’s quite the game…

SF: Buzkashi is an amazing sport. These guys are 12 feet tall on horseback and they look like superheroes. In America kids dream of being NBA superstars; there kids dream of being buzkashi riders.

DFI: Do you miss Afghanistan?

SF: I do. Afghanistan is definitely lodged in my heart. I want to make sure the people who we’ve tried to support as much as we could continue to [get our assistance]. I’ll be back, definitely – hopefully sooner rather than later.

DFI: What are you working on next?

SF: We’re going to do a fundraising round for the Afghan Film Project to continue our training programmes and I am trying to write a feature film set in Afghanistan. I think there’s an opportunity to make a film that highlights the things that I see and love about Afghans and Afghanistan that you don’t see in major films, [because] what Hollywood likes to do is make films about soldiers or war. I also want to show some of my experiences there after five years. And I’m continuing working on my documentary production company.

DFI: So you’ve got a couple of things to do then…

SF: A couple of things to do, yes. Not done with the place!